The etymology of the word ridicule comes from ridiculum, a Latin word meaning “laughable.” Naturally, this has also given us the word ridiculous. But somewhere along the word’s journey from ancient Rome to present day, the concept of contempt stuck itself to ridicule.

Ridiculous managed to dodge contempt in all instances — except wine.

I mention this for a few reasons. Is there anything more ridiculous than this:

#BS #TastingNotes of the Week: “cold bonfire” & “well-hung game.” Both used by W.A. to describe a Chilean Syrah. #awesome

— Opening a Bottle (@openingabottle) February 3, 2016

Or these:

#BSTastingNote of the Week (not fake): “Youthfully imploded dark fruit flavors.” How does youth implode? Or how does 1 implode youthfully? ????

— Opening a Bottle (@openingabottle) November 3, 2016

#BStastingnotes “an intense, lasting feeling of plenitude” followed by “hillside tea” …from a very self-congratulatory winery

— Jackson Rohrbaugh (@jacksonwr) November 11, 2013

The source of these ridiculous displays of pomposity is an archetype: The Wine Snob. And those who use such language are likely the very ones who show contempt for certain wines and certain wine drinkers.

It is ridicule without any awareness of the ridiculous. A jolly object (wine) reduced to a humorless enterprise.

So are tasting notes dead or just broken and in need of fixing?

Self-aggrandizement has effectively rendered the practice of tasting notes useless. I don’t know what’s worse: that beautiful wines are not given the precise language they deserve, or that this ridiculous “winespeak” has repelled millions of people from otherwise learning and loving wine.

It would be all too easy to blame the problem on the practice of evaluating wine, rather than an epidemic of lazy (or irritatingly extravagant) writing by wine tasters.

However, in the end, there is a very real need to describe wine. Beautiful wines ought to be shared. But there are so many out there, we ought to give specifics on why each one is worth the time and money.

So what should wine writers do to better help you, the consumer? I think we can reform tasting notes for the better by doing a few simple things.

1. We need to make it known that wine is open to interpretation from everybody

What happens when we smell a distinct aroma or pick up a certain flavor in a wine? Are we saying that a Chardonnay has lemons in it, or are we saying that it reminds us of lemons? The former seems to be a suggestion that they share a common chemical compound that can be proven with science. The latter suggests more of a mystery.

So which of these two approaches is more inviting to a newcomer?

Without question, it is the latter. Professional wine tasters speak with certainty, because without it, they don’t have expertise. Yet, that “expertise” is heavily influenced by context and personal bias. And if you aren’t a professional, you won’t experience the wine in the same manner.

Could that same lemon note in a Chardonnay come across as limes to another drinker? Absolutely. What if its more specific, like lemon cream pie? Or lemon drop candy? By removing truth from tasting notes and inviting mystery, we are inviting a conversation. We are removing barriers and reducing snobbery.

We are also doing our part to eliminate contempt and ridicule.

So the first part of the solution is easy: If wine writers were to insert phases such as “reminds me of” or “recalls“ into their tasting notes, they would force themselves to be more humble, and — more importantly — give their wine description more credibility and usefulness.

2. We need to remove “truth” from the process

Let’s return to etymology for a moment. Ever heard the phrase vino et veritas? It is often dropped by wine people — with gobs of conceit no less — because it directly means (there is) truth in wine.

But a recent article by Jeremy Parzen on the University of Gastronomic Sciences website dove into how this phrase is so chronically misunderstood. As he points out:

What the Romans appreciated — yet we lost somewhere along the way — is wine’s ability to skew our senses and thoughts toward a more jolly place.

In fact, when you look at the meaning of the phrase through this lens, the notion of wine revealing an empirical truth is patently ridiculous.

3. We need to make our standards clear

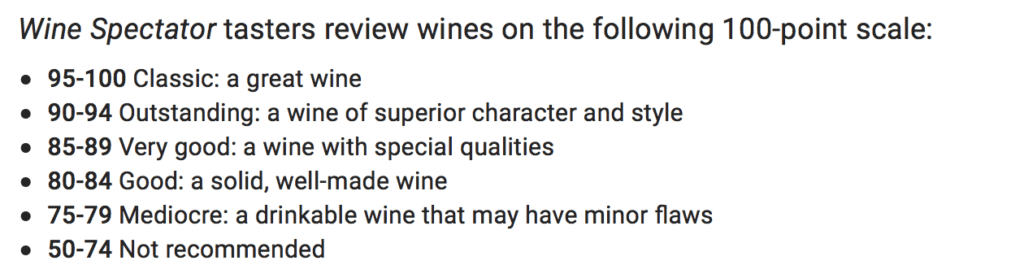

It amazes me how difficult it is to find a clear definition of a wine publication’s standards for assessing wine. Not to pick on Wine Spectator solely (Wine Advocate and Wine Enthusiast provide similar vaguery), but you often see things like this.

I want to ask “based on what?” after each one of those rating tiers. For some tasters, bigger and bolder is better. For others, the way a wine complements food is its true hallmark. And then you have those who like their wines to be esoteric.

With that in mind, what does “classic” mean? Answer: three different things to three different tasters.

I’ve tried my best to make my ratings and standards clear on this website, and I frequently revise the pages because my criteria constantly needs refinement (it’s far from a perfect method), and because my tastes change (yep, I’m just like everybody else). My interests vary from year to year, and that’s OK. At least you know where I’m coming from, and whether my tasting notes will resonate with you personally, or not.

4. We need to better convey the magic of great wines

If we can establish that wine is open to interpretation from everyone, that we are not the sacred keepers of “wine truth,” and that our standards for evaluation actually mean something unique — only then will tasting notes be helpful to read.

And I think it is important to acknowledge when a wine has us delightfully flummoxed. Sometimes the thrill of a great wine lies in the little surprises it reveals.

People often laugh when a wine writer describes a wine as having notes of “wet rocks.” Obviously, no one wants to lick a wet rock, not even the conceited guy describing the wine. But isn’t it wonderful to step outside after a rainstorm and smell the wet earth? Or to stand along a stream and notice how alive your sense of smell is?

The fact that a wine can surprise us with such an experience — and maintain a deliciousness that invites you to take one sip after another — that’s some magical stuff right there.

Suddenly, “wet rocks” doesn’t seem so ridiculous. Suddenly, I’d like to try that wine.

But it takes time to explain this. If we are going to be effective wine writers, we all need to embrace our job as storytellers and reveal these strange surprises in greater detail. Simply saying “wet rocks” (which I have done a bunch of times!) doesn’t cut it for the majority of people out there.

5. Finally, we need to evaluate fewer wines with more attention

Doing all of this in a mass-tasting setting is impossible. But I have a simple fix for that: stop doing mass tastings.

Sipping 50 to 200 wines in a day and properly evaluating them is detached from reality. It’s not how wine is consumed. Would you believe a Road & Track car review if all they did — in the interest of reviewing 200 cars in a day — was sit in the interior and pretend to drive the car?

It is far better for us to review wines by the bottle with a meal, because that is the most common context with which you’ll consume the wine, right? If that means wine writers should (a) consume less wine in mass tastings, and (b) take the time to evaluate how a wine changes over an evening or two, then so be it. That can only be a good thing for our readers.

As for consumers, my advice is to find a good wine writer who speaks to your heart and follow their advice. The good ones take their time with wine, and their evaluations show it. Hopefully, I am one of those people, but if you feel that I am not, I take no offense.

Personally, I know I have improvements to make to become the wine writer I aspire to be. But the more I do this, the more confidence I have in taking time with each wine, and evaluating them with these things in mind.

I hope it shows when you buy a bottle I recommend. For me, that would be the biggest accomplishment of all.

Thank you for the mention. “Find a good wine writer.” I’m glad to have found one in you! Sound advice and great post.

Thanks Jeremy. Likewise. Hope we cross paths at a wine tasting sometime.

Well written. It has us conversing over dinner about the crazy wine reviews we’ve read.

Bravo! Excellent points made in this article. Good luck with the Blog Awards!

Excellent article! So many great points- especially Point #5…so lets stop evaluating mass quantities of wine in one sitting and publishing the results. I doubt anyone (of credibility) does that with fine art or classic automobiles- my opinion of most wines.

Well written. Good points. It is always a challenge to use vocabulary fitting to your audience, in my experience. I am a Somm (woop woop), and as such had to learn the descriptors required to attain certification. I teach at a local college, as part of the culinary arts program. My students have a vast array of wine knowledge, mostly not a lot. First class I always advise, that like anything new learned, there is an associated vocabulary also learned. From accounting to karate to yoga to wood working, there are new words learned. I am also the president of a quickly growing NFP wine society. Members wine knowledge ranges from “professional” to “love wine, want to learn more” . In the end, it’s all about knowing your audience and speaking with respect, and definitely light hearted fun. When I’m with my Geek wine friends we get right into it, eventually laughing at ourselves. When I am addressing a mixed crowd, it’s all about accessible language, engagement, and ensuring no one feels excluded. In terms of understanding wine scores and writers and what they mean, to my mind it’s understanding your own preferences and evaluating based on that. My palate preference varies greatly with the Wine Spectator genre, for example, so I take that into consideration when considering wines reviewed by them. And, finally, preaching to the choir about massive tasting binges, including award competition binges, Er, I mean wine competitions.