It all began with a bottle of Brouilly from Château de la Chaize. Or was it a Juliénas from Pascal Granger? Or maybe it was the Moulin-à-Vent named “Couvent des Thorins” from Château du Moulin-à-Vent?

At some point, a few years ago, I hopped on-board the bandwagon and became a BeaujNerd, a CruHead, a Gamayniac. And unless the quality of the region dramatically dips (and there’s no reason to see why it would), I’ll be on board for life. There is something about Cru Beaujolais wines that is so transparently beautiful and easy — to me, they are the friendliest entry point for novices to French fine wine.

So when I first laid eyes on the granite hills of Beaujolais a few weeks ago, I’ll admit that I was giddy. It didn’t matter that the light was failing after an exhausting day of travel: the landscape of steep hills, stubby bush vines and intimate villages tucked into ravines immediately felt familiar.

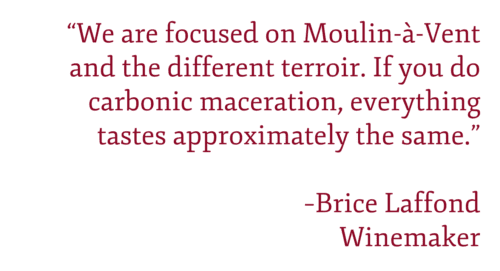

My group was headed to Château du Moulin-à-Vent, an historic estate that was once the domaine of reference for Beaujolais’ most prestigious Cru. But complacency and neglect throughout the late-20th century led to a steady decline of the estate’s wine. Its purchase in 2009 by the Parinet family has resurrected its reputation in remarkably quick fashion. Their version of Gamay Noir is strong, complex yet still agile, and their recent adventures with Chardonnay in nearby Pouilly-Fuissé look very promising.

I was already quite familiar with their wine, but seeing a winery first-hand will always put its wines in better context. The estate seemed like the perfect starting point to advance my education on Cru Beaujolais.

A Beaujolais Welcome

But we were late for dinner. As dusk fell, I had to enjoy my first impressions of the Cru’s icons from the passenger window of a speeding car: the oak tree atop Morgon’s Côte du Py, the chapel at the summit of Fleurie’s slopes, and finally, the iconic windmill of Moulin-à-Vent, located just down the road from the estate. Illuminated in lights, the 500-year-old structure was breathtaking.

“When we talk about terroir and Moulin-à-Vent,” Edouard Parinet told me later that night, “all you have to do is ask: why is the windmill here? Wind is the defining factor of Moulin-à-Vent. Because the vines are dried by the wind, and the berries, as a result, are more concentrated.”

Moulin-à-Vent’s pink granite is also a contributor to the appellation’s famous intensity. But such an easy-to-grasp explanation of terroir — “it’s windy” — simply reaffirmed why I love Cru Beaujolais. It’s special ingredients lend themselves to an easy romance.

“Perhaps tomorrow we will go for a drive,” Edouard elaborated. “When you are up above, you can see how Moulin-à-Vent faces the wind. It is very clear.”

Dinner was served in the estate’s adjoining dining room, an intimate parlor of sage green hues and beautiful wood beams. After several days of dining in restaurants, it was wonderful to have a family-style meal, and to relax in someone’s home. It felt like the mood of Beaujolais’ wines.

As our evening drew to a close around 1am, we took a walk through the Clos de Londres vineyard that reaches out to the windmill behind the estate. In the darkness, we navigated around ankle-twisting depressions and vines to stand beneath the hulking windmill. Immobilized long ago to protect its structural integrity, the windmill is in immaculate condition. And in the morning, we’d see what wind-driven terroir really meant.

Ambition in the Winery

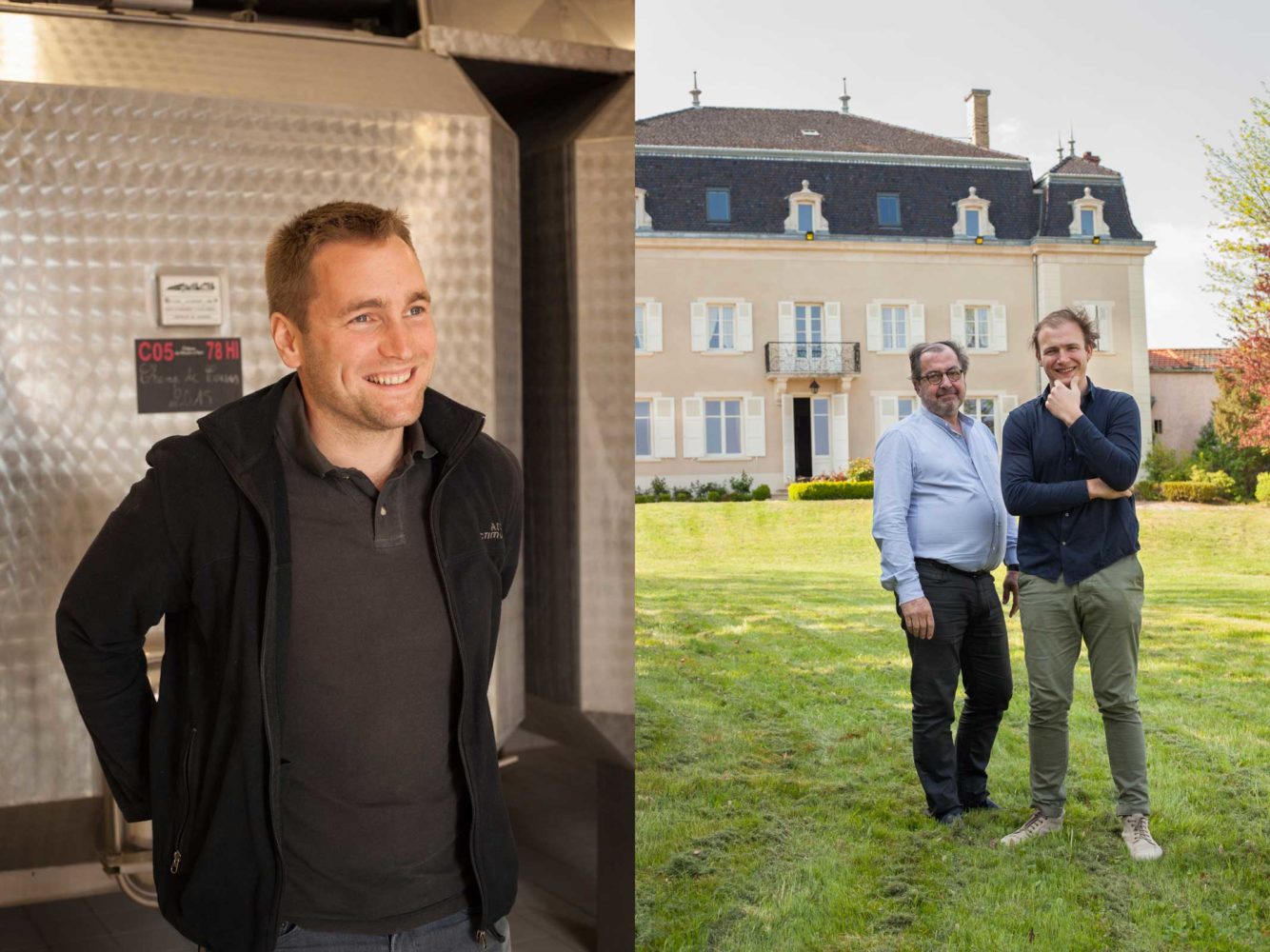

We started the next day with a tour of the winemaking facilities with Edouard and his winemaker, Brice Laffond.

Brice has a youthful appearance but his temperament conveys his experience. He had been reserved throughout much of the previous evening, but in the winery — among stainless steel tanks and oak barrels — he seemed more at home.

It would not be a stretch to call Brice a viticultural prodigy. He conducted his first harvest as a winemaker for a small family estate in Champagne at the age of 18. His arrival at Château du Moulin-à-Vent in 2012 followed stints at Château Mouton Rothschild in Pauillac, Domaine Faiveley in Nuits-Saint-Georges and Spring Mountain Vineyard in Napa. Now 29 years old, he is defining the prime of his career by mastering the nuances of Beaujolais’ most celebrated Cru.

“We are trying to make, more and more, the expressions of each vintage,” he told us. To do this, they destem the clusters for the single-vineyard wines, and avoid a technique that for decades has defined Beaujolais: carbonic maceration.

“We are not really fond of carbonic maceration,” Brice continued. “Because the impact of this process is too big in the nose, in the taste of the wine. We are focused on Moulin-à-Vent and the different terroir. If you do carbonic maceration, everything tastes approximately the same.”

Even minus this technique, it quickly became clear how complex Brice’s operation is. Each vintage, he oversees the vinification of five — sometimes six — different Moulin-à-Vent. Three or four of them need to be carefully handled and sorted as single-vineyard wines. His team of 60 people can harvest five hectares in a day, giving them roughly five days to bring in all of the estate’s Gamay Noir clusters. Choosing which plots to harvest in what order requires significant vigilance and attention to detail.

Even minus this technique, it quickly became clear how complex Brice’s operation is. Each vintage, he oversees the vinification of five — sometimes six — different Moulin-à-Vent. Three or four of them need to be carefully handled and sorted as single-vineyard wines. His team of 60 people can harvest five hectares in a day, giving them roughly five days to bring in all of the estate’s Gamay Noir clusters. Choosing which plots to harvest in what order requires significant vigilance and attention to detail.

On top of that, there is a collection of Chardonnay wines to make from neighboring Pouilly-Fuissé. They have been making a cuvée of Pouilly-Fuissé for a few vintages now, but the Parinet family’s recent acquisitions of nine different lieu-dit in the area shows a commitment to upping their game, as well as being more than just the domaine of reference for Moulin-à-Vent.

I barrel-tasted the 2016 Chardonnay from four of these vineyards. With their unique characteristics and refreshingly clean profile, they have the potential to be just as interesting as Château du Moulin-à-Vent’s red wines.

But the Pouilly-Fuissé present an interesting wrinkle for the estate. According to French wine law, they cannot use their estate name on the label because it includes a different appellation’s name, leading to the natural question, “is this wine a Moulin-à-Vent or a Pouilly-Fuissé?” Whether they come up with a new brand name or stick with the simplified “CMV” moniker in the long term remains to be seen, but the endeavor is worth keeping an eye on.

“We don’t know yet if we will make a bottling of each lieu-dit, or not,” Brice said, thief in hand. Then he smiled. “It is tempting though.”

A Broader Spectrum

“I want to try something,” Edouard said to our group, a concealed bottle in his hand. Soon, our three glasses were filled with three red wines, and all we were told was that they were from the same vintage. Of course, one of them was from Château du Moulin-à-Vent. I was confident that I knew where this was going.

On the first wine I wrote down: “bananas,” “light,” “cherry-apricot.” On the palate, it was ethereal yet playful, with meaningful acidity. For the second wine, “forest, autumn and raspberry.” It was a bit funky on the palate, with a distinct savoriness. “Medium weight with a chalky finish,” I added.

The third wine was crystal clear: “elegance, tobacco, black cherry, minerality on the finish.” This, I knew, was from Château du Moulin-à-Vent. I’d had it before and it was recognizable. Compared to the other two, it was more complex and refined, showing greater depth and potential.

“Fleurie, Morgon and Moulin-à-Vent,” I guessed.

I was wrong. By a mile.

I had convinced myself that he was presenting us a lesson in Beaujolais’ terroir, but in fact, Edouard’s sights were set a little higher. The first wine was a Pinot Noir from Gevrey-Chambertin, which is home to some of Burgundy’s most famous vineyards (and yes, I thought it smelled like bananas. Because it did). The second wine was even more startling: a Syrah from the esteemed Côte-Rôtie in the Northern Rhône. A second tasting verified that it was lighter than the Moulin-à-Vent, which was the third wine (I shouldn’t get points for that … Any showman is going to put his wine last).

For Edouard, he was demonstrating that the wines of Château du Moulin-à-Vent are complex enough to reside in France’s upper echelons of wine. But for me, the exercise revealed something quite different. Like many wine consumers, I have always pinned Gamay Noir to a narrow swath on the red-wine spectrum: far to the left, under the words “light bodied.” Sure, there were some shades that were clearly darker (namely Morgon and Moulin-à-Vent), but my assumptions continued to label them as light to medium in structure. (It’s funny how a lack of tannin can fool you in this way).

In truth, the swath that Gamay Noir occupies on the spectrum is much wider, even overlapping with Syrah, which is widely considered a full-bodied wine.

At the table, this means a great deal. Because of their refreshing acidity and low tannin, the wines from the Cru of Beaujolais are naturally versatile. However, I have always shied away from pairing them with beef or lamb, the traditional stomping grounds of my favorite heavy-hitters: Syrah, Nebbiolo and Sangiovese. Knowing the exact range that Gamay Noir occupies means knowing the exact range of its pairings as well. It’s broader than we assume.

Completing the Picture

After the blind tasting, we huddled into a Land Rover and went for a drive to see the landscape. In this portion of the Beaujolais hills, the dominate soil type is a crumbly pink granite that is known as gore. Traces of manganese within this soil seem to increase the potency of the Gamay Noir berries, yielding to its brooding flavors and intense aromas. It was early April, and signs of spring were everywhere, but without ample vine foliage, the granitic soil created a peachy palate for the landscape. The hills looked a little like folds of flesh.

“It is uncommon in France to have a vineyard on granite,” Edouard noted as we stepped out onto a ridge and sprawled a map of the appellation on top of an empty stemware box. Rocks were laid on the map’s corners to keep the ferocious wind from blowing it away.

To our left, a steep hillside interlaced with vines faced the sun. This was the northern edge of the neighboring appellation of Fleurie. One of the Cru’s biggest surprises is how different the wines of Fleurie are from those of neighboring Moulin-à-Vent. Delicate, floral and feather-light, Fleurie plays the part of soprano to Moulin-à-Vent’s baritone. But all that separates them on a map is a meager stream.

However, there are huge differences in topography. Fleurie’s heights and steep slopes mean significant drainage and diurnal swings in temperature are more at play. Meanwhile, Moulin-à-Vent is a low, gradual slope that juts up from the valley just enough to take the full brunt of the Saône River Valley’s winds. Five-hundred years ago, the wind presented an opportunity, so a handsome windmill was erected. Today, that opportunity is complex wines that give Pinot Noir and Syrah a run for their money.

“I thought we could taste the wines here because it is a nice spot, but…” Edouard looked around for a place where we could be shielded. “Let’s go back and we will taste there.”

Even when it comes to picnics, the wind will always be a factor in Moulin-à-Vent.

Tasting Impressions

2015 Château du Moulin-à-Vent “Couvent des Thorins”

Moulin-à-Vent AOC, France

Grapes: Gamay 100%

Alcohol: 13%

Rating: ★★★★ 1/2 (out of five)

Impressions: Perhaps the only wine in Château du Moulin-à-Vent’s portfolio that I would describe as “light-hearted” and “fun.” Shows aromas recalling cherries, roses, oak and roasted nuts, yet demonstrates a light, mineral touch on the finish. Great textural quality. Seems to be the bridge that unites Château du Moulin-à-Vent with other Cru Beaujolais, because from here on, things go several degrees bolder.

2014 Château du Moulin-à-Vent, Moulin-à-Vent

Moulin-à-Vent AOC, France

Grapes: Gamay 100%

Alcohol: 13%

Rating: ★★★★ 1/4 (out of five)

Impressions: The first wine in their portfolio that starts to venture into richer, more concentrated territory. You notice it on the nose, right away, as it seems to fill the nasal passages with a surprising intensity. I detected notes that reminded me of black cherries, tobacco, wet earth as well as game. On the palate, the presentation lingers for a long time. Great finish. This wine is a cuvée of several different plots around the appellation.

2014 Château du Moulin-à-Vent “Croix des Vérillats” Moulin-à-Vent

Moulin-à-Vent AOC, France

Grapes: Gamay 100%

Alcohol: 13%

Rating: ★★★★ 3/4 (out of five)

Impressions: The first single-vineyard wine we sampled is named after a Redemption Cross that stands in the vineyard. It was erected by locals as atonement for stealing from the church during the French Revolution. Made from 50-year-old vines that are rooted into pure sand, this wine tips the scales more towards savory elements than fruit on the nose, recalling roasted game and wet earth. The complexion of fruit is quite dark, reminding me of currants and blackberries. Definitely more tannic and concentrated on the palate, but firmly in control of its destiny.

2014 Château du Moulin-à-Vent “Champ de Cour” Moulin-à-Vent

Moulin-à-Vent AOC, France

Grapes: Gamay 100%

Alcohol: 13%

Rating: ★★★★★ (out of five)

Impressions: Sourced from a vineyard comprised of pink granite and clay, “Champ de Cour” is an expressive and gorgeous wine. Highly aromatic: I practically inhaled it I was so smitten. Recalls the aromas of a raspberry patch with hints of violets, and plenty of minerality. Paradoxically deep yet high-toned on the palate, this wine closely mimics Pinot Noir until the finish, which is distinctly Gamay Noir. Quite a bit of acidity. Great food wine.

2014 Château du Moulin-à-Vent “La Rochelle” Moulin-à-Vent

Moulin-à-Vent AOC, France

Grapes: Gamay 100%

Alcohol: 13%

Rating: ★★★★ 1/2 (out of five)

Impressions: Hailing from the highest vineyard in their range, “La Rochelle” is a true shape-shifter. I was a bit confused by the aromas, which conveyed raspberries and pâté, as well as iris. But after a few whiffs, its eccentricity steadily grew on me. Seemingly lighter in complexion than “Champ de Cour” or “Croix des Vérillats,” it conveys a bit of roasted walnuts on the finish.

2011 Château du Moulin-à-Vent “Clos de Londres” Moulin-à-Vent

Moulin-à-Vent AOC, France

Grapes: Gamay 100%

Alcohol: 13%

Rating: ★★★★★ (out of five)

Impressions: Sourced from the walled vineyard that stretches out from the château to the windmill, “Clos de Londres” is only made as a single-vineyard wine in exceptional vintages. In other years, it is blended into the cuvée Moulin-à-Vent. Here is the proof that Moulin-à-Vent gets better with age. Deeply perfumed, it closely resembled Pinot Noir. However, it was more embracing and friendly than Pinot Noir tends to be. I detected notes of raspberry, violets and hazelnuts on the nose. Gamay Noir is not particularly tannic, but here, they seem to be fairly pronounced, even with six years of age. Put simply: a beautiful wine.

Note: My visit to Château du Moulin-à-Vent was part of a press-trip by their importer, Wilson Daniels. Learn more about our editorial policy.

One Comment