Our magnetism to wine often stems from a fascination with the elements. Grapes can transmit the sharpness of a cool climate or the tawdriness of a heat wave. The smooth texture of chalky soil or the bountifulness of loam. If you’ve heard this sort of thing before, but never felt it, it is time to check out the red wines of the Etna Rosso DOC in eastern Sicily. Here, a unique equation of elements adds up to one of the world’s most dramatic wines.

“In wine, we often abuse the term ‘sense of place.’ But I strongly believe that Etna wines clearly have a sense of place.”

—Antonio Benanti, Owner, Benanti Viticoltori

“Suspend any expectations,” advised author and Etna wine expert Benjamin North Spencer when I reached him via Zoom for this article. I had asked him what newcomers to Etna Rosso should expect for their first taste. “The joy of Etna’s wines shows in their variability,” he told me, detailing how a light-colored Etna Rosso can be powerful, while a darker one could have a different tenor entirely.

Spencer moved to the slopes of Etna in 2012 to pursue his passion for these wines. He has since founded the Etna Wine School and written the ultimate guide to the volcano’s wines, The New Wines of Mount Etna. His book showcases not only the diversity of winemaking styles and terroir on the mountain, but it also chronicles the distinct signatures left on the wine by the dynamism of ash and lava which has spread across Etna’s slopes for eons.

“Even in one place, you can taste something quite rustic, or something that is very elegant and refined,” he said. “You will taste things that will make you curious, and that will reinitiate your wonder with wine.”

Antonio Benanti — who, along with his twin brother Salvino, is co-owner of the iconic Benanti winery — pulled no punches when we kicked off our conversation on Etna Rosso. “In wine, we often abuse the term ‘sense of place.’ But I strongly believe that Etna wines clearly have a sense of place.”

Benanti has a valid point. on two fronts: For one, most wines reveal nothing in terms of terroir, no matter what the marketing says. Secondly, when Etna’s wines are on point, there is no mistaking them. They are violently aromatic, they are savory and earthy and frequently quite herbaceous. Their acidity cuts like a laser.

This month, I finally got my chance to visit Mount Etna and meet several of its winemakers in situ. My impression of Etna was of a place forged by four or five key elements, but the truth is far more complex: this place is a 50-sided Rubik’s cube. Combined with the sizable talent found on its southern, eastern and northern slopes, Mount Etna is easily one of the world’s most dynamic and compelling places for wine right now. Etna Bianco is among the world’s greatest white wines, and is poised to be so for generations. Several Etna Rosato I tasted could rival any rosé on the market.

But it is Etna Rosso that remains the headline grabber, as it has helped nudge all of Italian wine into an exciting new phase. As this Sicilian appellation has embraced its singular identity — and climbed the ranks of fine wine worldwide by refusing to conform to “international style” — so too has the rest of the country. Who wants to talk about Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot from Maremma when we could discuss Nerello Mascalese and its alchemy with ash? Or Grillo and its salty splendor, Aglianico and its bitter fruit, or Timorasso and its tannic loveliness as a white wine? Eccentricity is Italian wine. Only now is it becoming the global phenomenon it deserves to be, thanks in part to places like Etna.

So what is the 101 on Etna Rosso? How are these wines made and why are they so wild? And who should you seek out for that first taste? Let’s sweep aside the ashes and take a look with this revised and updated guide, which was originally published in March 2021.

3 Reasons to Try Etna Rosso

- Because Everyone Needs to Experience a Volcanic Wine Once – Volcanoes are the Earth’s most visceral reminder that forces greater than humankind are still at work. They can take life (see: Pompeii), and they can give it (see: the likely volcanic origin of the beans in your coffee this morning). In wine, volcanic soil provides razor-sharp acidity; a tingling, lively texture; and significant depth of aroma. Given the youth of many of Etna’s soils, these traits are amplified to a point that even novices can notice the volcanic signatures. (See below for my recommended wines).

- This is Among the Most Dynamic Wine Regions on Earth – The only reason to try a new wine is to potentially fall in love with it, right? If Etna Rosso registers beautifully for you, a whole lifetime of tasting awaits. This vast, crescent-shaped region has a wealth of quality producers and singular terroir to explore, and it is only just now getting fully charted, studied and understood.

- It Is One of Italy’s Top 5 Wines. Period. – Looking for greatness? Etna has it. Perhaps the reputation is not as large as Barolo (yet?), and the stature is not as tall as Brunello di Montalcino (yet?), but Etna Rosso’s greatest wines can contend with them. And the potential for long-term aging is absolutely tantalizing.

What is as an Etna Rosso DOC Wine?

To qualify for the Etna Rosso DOC, wines must come from within the delimited zone on the northern, eastern and southern slopes of Sicily’s Mount Etna (between 1,000 and 3,600 feet in elevation, or 1000 to 3300 meters). The wine must be comprised of at least 80% Nerello Mascalese, with up to 20% Nerello Cappuccio allowed. Wines must be a minimum of 12.5% alcohol-by-volume (ABV), and a variety of winemaking techniques are allowed per the Etna Rosso guidelines. While there are no aging requirements, an additional riserva designation is included for wines with a minimum 13% ABV level and four years of aging with at least one year spent in a wood vessel.

About the Appellation and Its Wines

When I first wrote this guide in the spring of 2021, Mount Etna had been in a foul mood, with a particularly active period of eruptions. Lava fountains reached 2,000 meters into the air, and ash plumes carried over much of Sicily.

Eruptions like this have been very common in recent history, so much so that the summit of Etna dropped by 25 meters after an eruption in 2018, only to be replenished by another 31 meters to a new record height in 2021. Today, the summit stands 11,000 feet above the adjacent Mediterranean Sea.

Author Benjamin North Spencer shared one of these ashy “rainstorms” on twitter in 2021. Turn the sound on for full effect.

One of the perks of living on Europe’s largest active #volcano. Spontaneous soil and rock deliveries. #Etna#amwriting #amlivingonavolcano pic.twitter.com/BTOLg0sWqR

— Benjamin North Spencer (@WordsnWine) March 7, 2021

Throughout its history, Etna’s most devastating eruptions have been from lava flows, and they don’t always originate at the summit. As we drove near Randazzo, a sudden change in the landscape revealed the remnants of a 1981 eruption that swallowed several vineyards. That flow had started well below the summit when lava was forced to the surface and exposed.

The mood swings of the volcano are simply part of the terroir. Tenute delle Terre Nere owns a small clos-like parcel called Dagala di Bocca d’Orzo, which is almost entirely surrounded from the 1981 eruption. Such are the stories you find when you rummage around the wines of Etna.

On a webinar I attended about his Etna Rosso wines, Alberto Tasca, Managing Director of Tasca d’Almerita, described his mixed feelings about Mount Etna when they initially established their Randazzo-based estate, Tascante. “I can tell you that when I signed the contract for the first piece of land, I didn’t sleep,” he recalled. “I was totally awake because I was a little afraid of the power of the volcano.”

That’s not to suggest winemakers work in a constant state of fear. But the volcano certainly demands a level of respect and diligence that makes winemaking on its slopes unique to the wine world.

The Terroir & Toil

To understand why these wines are so unique, the first place we need to go is underground. Yes, the soil is almost entirely volcanic, but that doesn’t mean it is heterogeneous. For the last 15,000 years, a sequence of eruptions has left tongues of rock and ash across Etna’s flanks. The age of these soils — which are very young geologically speaking — often lend the wines varying degrees of vibrancy.

That’s because nature has devised a brilliant, centuries-long process that eventually converts the newborn lava into sandy soil suitable for plant life. Because of this steady, consistent process, different lava flows from different eras are at different stages of fertility.

This conversion process begins with lichen and moss. They essentially soften the rock enough for “pioneer plants” — such as ginestra, sorrel, grasses and fir trees — to take root. These hearty plants go to work on the rock, breaking it apart and separating it with their growing roots. As these plants die, they add organic material to the soil, until eventually, the terrain is hospitable for more and more types of life forms. Just how far along the soil is in this process of decomposition will help determine everything from the soil’s ability to retain water to what kinds of microorganisms are present.

Spencer estimates that a lava flow will require roughly 500 years of decomposition to become suitable for grape vines, but, he adds “that depends on how thick the rock is, if it was from an effusive lava flow, if it was stone that had been thrown from the crater, or if it was just a lot of ash and lapili — then obviously it will be more sandy.”

Among wine regions, this process is not entirely unique to Etna, but it is certainly an area where the interrelationship between lava flows and vineyards is as visible to the naked eye as anywhere. More importantly, it is also where this relationship is most decipherable to the palates of everyday wine drinkers.

“The place itself has a stronger impact on the resulting wine than the variety,” Antonio Benanti told me. “Regardless of the wine being red of white, you will find this high acidity, this earthiness, you will find a saline note, you will find elegance and length. Etna leaves a very clear mark on these wines.”

Both Spencer and Benanti suggested that these influences are acutely noticeable on international varieties grown on the volcano, such as Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. This is, in part, because we all have a baseline for what those grapes should taste like, and where those sensations divert is where Etna has meddled. However, those grapes are not allowed in the wine called Etna Rosso DOC. For that, you have to turn to a local hero: Nerello Mascalese (which we will get to in a moment).

The other key factors that makes Etna’s terroir unique are elevation and proximity to the sea. “Mountain wines from a Mediterranean latitude,” is how Benanti categorized them. The delimited zone for Etna Rosso lies between the 1,000 and 3,600-foot level along the mountain’s southern, eastern and northern flanks. Despite its location below the 38th parallel, the Etna wine region is a cool climate, thanks to this high altitude. Some Nerello Mascalese vineyards can be found above this mark, but their wines must carry a different designation (usually Terre Siciliane IGT) for falling outside the boundary.

So why is elevation so crucial? Simply put, it dictates two critical factors in ripening: ambient temperature throughout the year and overall luminosity from the sun, which is higher at altitude because of thinner air, but can be lower in some areas due to persistent cloud cover generated from the volcano’s heights. Mix this with the fact that the eastern edge of the zone is only four miles from the Mediterranean Sea, and you have a tapestry of conditions to work with. With slow-ripening Nerello Mascalese at the fore, that can mean a very long growing season that stretches into late October and even early November in some parts of the zone.

Lastly, the steepness of the slope has often led to terracing — one of the defining visual traits of the Etna landscape. Made from dry-stone walls, the terraces have made the slopes more manageable but their maintenance adds to the cost of labor, as specialized stone masons do many of the repairs.

The Importance of the Contrada

Because of this variability in conditions, efforts have been made to celebrate the 132 contrada of Etna — essentially the villages that dot the volcano’s flanks. While these wines are technically not single-vineyard (i.e. one contrada could have many different vineyards with different owners), they fit into the product mix like a cru-designated wine would. The multi-parcel blends and young-vine Etna Rosso are typically the affordable entry-point, while the contrada wines — with their specificity of terroir, and frequently older-vine parcels — are the more scarce, higher-end, often-times more expressive renditions of the wine.

For Alberto Tasca of Tascante, the contrada are more than just villages — they are a quintessential part of what makes Mount Etna unique.

“All these different eruptions have built the concept of contrada,” he observed. “The differences between one contrada to another one is the age of the lava flow. So in each contrada, you have some attitude [personality] because of the position of the contrada, the altitude of the contrada, and the composition of the soils.”

The Grapes and Blend

Indigenous to this part of Sicily, Nerello Mascalese (pronounced ner-ELL-oh MAHS-cuh-LAY-SAY) is hardly found anywhere else but on Etna, where an estimated 90% of the grape’s worldwide plantings can be found. While the volcano’s impact can be felt on many of the grapes grown on Etna, it is Nerello Mascalese that producers have come to prefer for quality-driven reasons.

“When people try Etna Rosso, the very first comment — which is somewhat superficial, but I think it is a compliment — is ‘this reminds me of Pinot Noir,'” observed Antonio Benanti. “Not only the appearance of the wine, but the feeling on the mouth — the precision, the mid-palate, the length.”

Like Pinot Noir, Nerello Mascalese has smaller-sized berries with a higher skin-to-flesh ratio, which helps to yield more character and complexity in the wine. And like Pinot Noir, it is a great translator of the elements from which it is grown. In the volcanic soils of Mount Etna — which Nerello Mascalese has adapted to — that registers as a wine driven by red fruit tones that pop on the nose and an intense herbal streak that might separate it from Nebbiolo and Sangiovese in a blind tasting. On the palate, Nerello Mascalese’s ferocious tannins come into play, but are balanced by generous yet not-quite juicy acidity, a mineral texture and a finish that often registers as mildly salty. And like something salty, Nerello Mascalese often makes you want to come back for more.

Pinot Noir can present similar tones, but think of the soil as a language and the grapes as actors reading a script. Nerello Mascalese is fluent in volcanic; Pinot Noir is still playing catch-up on Duolingo.

From a farming perspective, Nerello Mascalese has other advantages, too.

“Of the grapes on Etna, Nerello Mascalese is the one that adapts more easily to a broader range of conditions,” said Benanti. Unlike the white Carricante, which thrives mostly on the cooler, wetter eastern slope facing the sea — or Nerello Cappuccio, which prefers the south-facing slopes — Nerello Mascalese thrives all over Etna, but it struggles to ripen above 3,500 feet. Another advantage to Nerello Mascalese and its symbiotic relationship with volcanic soil: it rarely demands chemicals, so many of the vineyards on Mount Etna are practicing or certified organic.

“It is a late-ripening variety, so you have to hold your breath for a long time,” laughed Benanti. “But Nerello Mascalese is a variety that really lends itself to lower yields. And it is also less prone to diseases.”

When you take these factors into account, the quality of Nerello Mascalese begins to make sense: smaller berries and lower yields results in more concentrated character. To get the most from these grapes, they are typically planted as bush vines (i.e. alberello-trained) and in a higher density environment to encourage competition in the roots.

As for Nerello Cappuccio, its role in the drama of Mount Etna is as a supporting character, but it is critical no less. Darker, spicier and lower in tannin, under the right conditions it can be an important foil to Nerello Mascalese’s assertiveness. However, its tighter cluster on the vine makes it more prone to fungal disease and rot. Some producers avoid the grape outright.

“We never vinify Nerello Cappuccio in oak,” said Benanti, whose family also makes a varietal Nerello Cappuccio under the Sicilia DOC designation. “It [goes] in stainless steel only because there are no tannins that need to be refined. Again, it is such a unique variety, that it needs to be vinified in such a way to show its true essence.”

Even with their Etna Rosso DOC (detailed below), Benanti prefers to ferment and age the Nerello wines separately, and only assemble them before bottling.

Winemaking

The Etna wine industry is at once ancient and nascent. Viticulture on the volcano’s slopes dates back at least as far as the Greeks (roughly the 8th century BCE), and the wines were celebrated by the Roman Empire. Through the ups and downs of war, poverty and mass emigration, Etna’s vineyards found themselves largely in a state of abandonment by the second half of the 20th century.

Given the state of affairs in the area in the 1980s, the volcano’s wine renaissance through to today is nothing short of incredible. A mixture of homegrown estates (especially Benanti, but also Barone di Villagrande and Graci), curious Sicilians reinstating old family plots (Girolamo Russo and Biondi), Sicilian juggernauts (Tasca d’Almerita, Donnafugata and Planeta) and outsiders from mainland Italy and beyond (Passopisciaro, Frank Cornilessen and Marc de Grazia of Tenute delle Terre Nere) helped re-establish the mountain as the premier wine-growing area in Sicily.

But the early days of this renaissance — while defined by excitement and potential — saw a great deal of trial and error.

Benjamin North Spencer noted that a lot has changed on the mountain since he moved there in 2012, with the shift toward more hyper-local, terroir-driven wines being at the fore. “When I first got here, there was still this idea hanging on from the early aughts that wine should be guided into a sort of international style,” he told me. “But the more producers work on the mountain, the more they started to back away [from that ideal].”

An embrace of gentler winemaking techniques — such as cooler macerations and careful use of oak — has seen the wines evolves into a truer form. Another element of winemaking on Etna that gives it an advantage with modern tastes? The relative ease in growing organically in the vineyard, and the desire of many producers to use minimally invasive techniques in the winery. Intriguingly, the rise of natural wine has followed nearly the exact same timeline as the rise of Etna.

Your First Taste

Making a recommendation for your First Taste of Etna Rosso is almost as herculean a task as choosing the right first taste of Chianti Classico or Barolo. During my recent visit to Etna for the annual Etna Days event, I tasted more than 80 different versions of Etna Rosso, and was roundly impressed with a majority of what I tasted.

Since our first-taste guides always focus on broadly available, entry-level wines, I have steered away from the single-vineyard or contrada wines for the most part. Consider those your “next step” if you geek out over these wines.

I’ve also deliberately not included some of the awesome Terre Siciliane wines coming from Etna, notably Passopisciaro’s “tower of power” contrada series, and Calabretta’s fantastic, long-aged-before-release “Vigne Vecchie.” While they certainly carry Etna’s signature, they don’t say “Etna Rosso” on the label because they are outside the bounds of the regulations. A small detail to some, but to avoid confusion with this guide, I’m not including them.

The Icon: Benanti

For one, they are the winemaking house that started off a significant portion of the renaissance in the 1980s when no one was really looking this way for great wines. Their track-record is more extensive, and they have been very reliable over the past few vintages. They take their role as the protectors of Etna Rosso very seriously, and because of this, I sought out Antonio Benanti for this article). Few people can speak to what this place is about better than he, and I truly feel their wines reflect that. They are straight-down the middle on what Etna Rosso ought to be: classic, expressive, elegant, bold, detailed and age-worthy.

Get started on your Etna Rosso journey by tasting their Benanti Etna Rosso (★★★★ 3/4). Comprised of 80% Nerello Mascelese and 20% Nerello Cappuccio, it has less of the astringency of other entry-level wines, yet all of the unique characteristics of the volcano: a wine decked in morello cherry tones, streaks of mint and a pleasant ash-driven earthiness. It’s mineral finish is another superb indicator of its volcanic origins, but don’t be surprised if a few sips remind you of Pinot Noir. This is a great first taste of Etna Rosso for all the criteria it fulfills.

As a next step, ramp things up a bit with the Benanti Contrada Cavaliere Etna Rosso (★★★★★), a stunningly intense yet balanced wine that shows the potential for power and finesse on Etna.

Benanti: An Essential Winemaker of Italy

The Easy to Find (and Still Emblematic): Donnafugata & Tascante

Planeta, Tasca d’Almerita and Donnafugata all have a presence on Etna. These three major wineries are often the leading ambassadors for Sicilian wine in primary and secondary markets of the U.S., and as a result, I always stay in touch with their wines due to availability.

Donnafugata’s Etna Rosso, called “Sul Vulcano” (★★★★ 1/2), has made some giant leaps forward since I last tasted these vintages four years ago. Carrying that signature Etna Rosso profile of refreshing dark cherries and minty herbaceousness, it has silky acidity and lean little tannins that make the wines highly versatile at the table. This is a classic Etna Rosso, and a nice starting point.

If you are looking to explore Etna’s other categories of wine, notably the rosato, Donnafugata’s “Sul Vulcano” Etna Rosato (★★★★ 3/4) is a superb, silky textured rendition and one of my favorites.

Tascante is the name of the Tasca d’Almerita estate on Etna — a play on the family name meeting that of the volcano. Tascante’s “Ghiaia Nera” Etna Rosso (★★★★ 1/2) serves as the entry-level wine and it relies on 100% Nerello Mascalese sourced from their young-vine holdings in the Sciaranuova and Pianodario contrade on the north slope — both places known for their power. Look for Etna’s signature acidity and bursting fruit.

If you see any of Tascante’s three single-contrada Etna wines while you are shopping, note that the Contrada Pianodario (★★★★ 3/4) is particularly good with balanced structure and phantom tannins that only assert themselves on the finish.

The Wild Side: I Custodi delle Vigne dell’Etna and Azienda Agricola Biondi

At the moment, my two favorite producers on Mount Etna are I Custodi delle Vigne dell’Etna (literally “the custodians of Etna’s vines”) and Azienda Agricola Biondi. Both estates offer the “most volcanic” expressions of Etna Rosso and Etna Bianco.

What exactly do I mean by that? Like the ever-changing summit of the volcano, the wines of I Custodi (and to an extent Biondi) are dramatically different from year to year, presenting new and thrilling details with each vintage, not as a result of winemaking, but rather of vintage expression. And in the end, that’s the promise of Etna that I feel us wine drinkers want fulfilled.

I Custodi’s entry-level Etna Rosso, called “Pistus,” is a consistently excellent introduction, with the recent vintage of 2021 (★★★★★) registering as the best in class at Etna Days. Vinified only in stainless steel and comprised roughly of 80% Nerello Mascalese and 20% Nerello Cappuccio, it eagerly provides the cherry-and-mint core of Nerello’s fruit, with a juicy yet edgy acidity that carries through to near perfect tannins, even at this early stage.

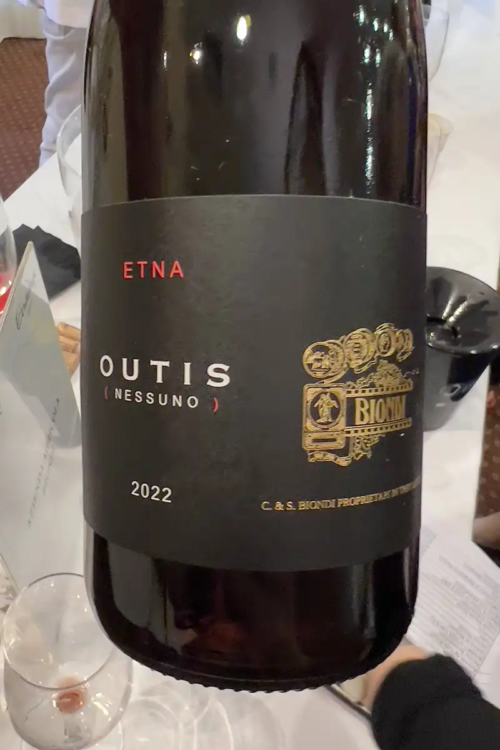

Biondi’s entry-level is called “Outis (Nessuno)” (★★★★★) or “Nobody,” which is a reference to the name Odysseus gave the Cyclops in The Odyssey. And guess where the Cyclops lived? In a cave on Mount Etna. Also an 80%/20% blend of Nerello Mascalese and Nerello Cappuccio, “Outis” is a prime example of Etna Rosso’s minerality. Look for it on the mid-palate and finish; it is an evocative sensation that might remind you of a rainstorm on a hot day. Biondi’s tannins across all three Etna Rosso are fairly coarse in youth, a bit like burlap right out of the bottle. But I don’t find them aggressive or assaulting, and they integrate beautifully with a little air. In my opinion, Biondi’s “San Nicolo” and “Cisterna Fuori” arm wrestle for the title of Most Compelling Wine on the Volcano from vintage to vintage. They have been Essential on Opening a Bottle for a few years, and my recent tasting at Etna Days reaffirmed that standing.

Biondi: An Essential Winemaker of Italy

Note: The wines featured in this article were tasted at a wine industry trade event held on Mount Etna in September 2023, and our Editor-in-Chief was invited as a guest from the Consorzio Etna DOC, which covered the expenses of travel but had no authority over the editorial content. Learn more about our editorial policy.