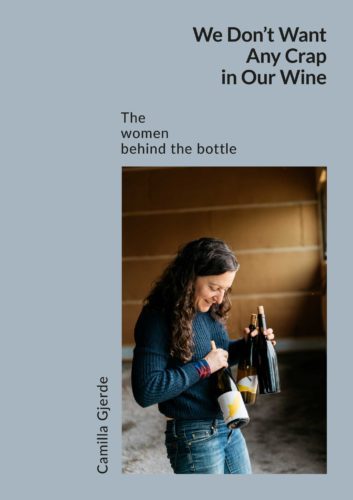

In this excerpt from her forthcoming book, We Don’t Want Any Crap in Our Wine, Camilla Gjerde explores how spontaneity and serendipity have shaped the career of Jura-based winemaker Alice Bouvot, whose expressive and ever-surprising wines can now be found on some of the world’s top wine lists. You can pre-order this beautiful book about the female winemakers who are shaping the natural wine movement in Europe directly from Camilla’s website. For this excerpt, the original British English text and style guidelines have been preserved.

Alice Bouvot opens her car door and says she is sorry about the smell. A bottle of red wine has leaked all over the passenger seat and she covers it quickly with her fleece jacket. Her dog Pistache is everywhere. We’re on our way from her home and old cellar in the centre of Arbois to her new winery outside town, a five-minute drive.

“In the beginning, nobody wanted my wines. Not even in Paris. In France they thought my wines were faulty. The first years were very hard. You were the reason everything changed,” Alice recalls, referring to us Scandinavians. “Especially Denmark. When some restaurants in Denmark started selling my wines, the French wanted my wines too.”

When word got around that the world-famous Copenhagen restaurant Noma served her wines, interest piqued. All of a sudden, the Parisian wine bars that are usually the trailblazers in the natural wine world, wanted her wines, as well as importers in the rest of Europe, Asia and the United States.

Alice now exports her wines all over the world: Taiwan, Japan, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, UK, Spain, Belgium, Australia, the United States. Since her cuvées are small and demand vastly outstrips supply, she allocates a limited selection of the wines to different importers, distributors, and restaurants. Today, you’re lucky if you can get hold of a couple of her bottles, that’s how popular she has become. But getting where she is today has been a struggle, and her way into natural winemaking — long and crooked.

A Music Lover, Animal Lover and Wine Lover

Alice grew up in Besançon, an hour north of Arbois, and she did not plan on becoming a winemaker. Alice played cello and piano, loved horses, used to ride every day and wanted to be a veterinarian. But when she failed the entrance exam, she opted for agricultural engineering instead. Having finished her engineering degree, she had no idea what to do and went to Bordeaux, because that’s what you do with this degree when you’re in France. In the wine capital Bordeaux, she took some wine courses and decided to pursue oenology studies in Dijon.

“It’s been very difficult to start from scratch, with two children. When Anatole, my youngest, was five weeks old I put him in a nursery forty hours a week because I had to work a lot. But making the kind of wine I want to make, you need to have your own business.”

Alice Bouvot

Winemaker, Domaine de l’Octavin

But even after she finished her winemaking studies, Alice still didn’t know what she wanted to do with her life. She ended up travelling the world for three years, working at wineries in California, Chile and New Zealand. At 30, Alice came back home to France and found a job in the Jura.

“I didn’t want to live in Bordeaux and I was worried I would think there were too many tourists in summer in the south of France. So I thought Jura, why not? It’s wonderful, you have Savagnin, Trousseau, you have many different grapes to work with. And I wanted children and then it’s good to be close to your parents.”

She worked a year for a domaine with 20 hectares of vineyards and met Charles Dagand who, at the time, was at the cooperative Fruitière Vinicole d’Arbois. They became a couple, and in 2005 the two of them decided to make wines on their own and started Octavin. Their dream was to make natural wines, and their shared love for opera and wine was reflected in the name of the enterprise and the cuvées, named after characters from Mozart operas: Dorabella, Pamina, Zerlina, Commendatore.

Ten years later, Alice and Charles split up, and since 2015, Alice has been the sole owner of Domaine de l’Octavin. She has had to make sacrifices and put in a huge amount of hours.

“It’s been very difficult to start from scratch, with two children. When Anatole, my youngest, was five weeks old I put him in a nursery forty hours a week because I had to work a lot. But making the kind of wine I want to make, you need to have your own business.”

Talks to the Yeast

Outside the winery is a crate full of empty bottles, all with the easily recognisable labels of Alice’s négoce wines: colourful garden gnomes and the occasional moose. A friend has drawn them, inspired by Alice’s garden which is full of small gnomes.

Alice’s wines stand out from the crowd, and not just because of the labels. She has chosen her own path. To her, winemaking is about integrity and having stamina. UK wine importer Tutto Wines describes Alice’s work as “both fanatical and fantastic.”

“I monitor my wines. I never touch them, I never do any pump-overs,” Alice says. This is minimal intervention and zero/zero winemaking: no sulphur, no pump-overs, no temperature control. Alice lets her reds macerate on the skins like an infusion, making wines with pale colour and little tannin, elegant and delicate, and bursting with energy. When she started l’Octavin with Charles Dagand, she used to extract much more from the grapes.

“Like everyone else, we thought we had to extract colour, tannin, wait a long time for the grapes to be really mature. But I realised that there are years when there is a lot of colour, and there are years where you don’t have colour. That’s nature and it’s beautiful.”

She now lets nature decide more.

“I have a more laissez-faire approach than in my first years at Octavin,” she explains and continues: “My zero-sulphur policy is like working without a safety net.”

Her approach is born out of what she likes and enjoys, and a conviction that sulphur kills something, makes the wines less alive. But it doesn’t mean that minimal intervention winemaking is easy for her. Alice was trained to intervene when anything went wrong in the cellar, so it’s much more difficult for her to do nothing than to intervene.

“Doing nothing is the hardest part. If something is wrong, you want to intervene. But I don’t,” Alice says. “Instead, you have to accept things the way they are, trust the grapes and trust yourself.”

Even when a fermentation is stuck and smells of rotten eggs. At most, she might add a bucket from another vessel to get a sluggish fermentation going. It’s usually enough to get it on the right track. But sometimes, she just talks to the yeast.

“Doing nothing is the hardest part. If something is wrong, you want to intervene. But I don’t.”

Alice Bouvot

Winemaker, Domaine de l’Octavin

“Last year, one of my vessels was reductive, it smelled of sulphur during the fermentation. I talked to the yeast and said, ‘Listen, sometimes I don’t want to get up in the morning either. I know life can be difficult, but you have to get out of bed anyway’. After that, the yeast started working again and the smell disappeared,” Alice explains with a smile, swirling a glass of Dorabella, her Poulsard.

It may seem eccentric, but if you see grapes and wine as living entities and acknowledge that a number of living organisms together create wine, talking to your fermenting must isn’t any stranger than talking to your dog. Still, it’s contrary to everything she learned as an oenologist. If a fermentation is stuck and smells reductive, you give it air, you put oxygen into the tank, you add yeast — and the fermentation finishes.

“I know that many would probably have intervened, but why always intervene? It’s hard to accept letting go, laissez-faire. Especially when you have a cuvée that is reductive. But you have to observe and be vigilant. When it’s vinegar it’s too late,” she says dryly.

What if it hadn’t started again, I ask. Alice shrugs.

“Normally it just takes time. It’s seldom that it doesn’t work, but there are certainly cuvées that are more difficult than others.”

The low-intervention approach of natural winemakers makes critics say natural wine has too much volatile acidity, that it tastes like cider, that it is oxidised. And that natural wine doesn’t show terroir, but instead masks it with mousiness or the farmyardy smell and taste of the Brettanomyces yeast. The same approach is what makes natural wine lovers say the wines are unique, full of life and energy, and express terroir in its purest form.

For Alice making natural wine is about being true to herself, to her ideals, to her taste and opinions. If people don’t like her wines, so be it.

“It’s all about being coherent. It should be my wine and if I like it, it’s perfect. And if somebody doesn’t like it, I don’t care. If you don’t like it, I will find someone else who does,” she says rather confidently before adding: “Of course, I have to sell. If I am the only one on the planet who likes my wines, I have a problem. I have to sell wines.”

Just Me and My Tank

To make the wines she loves, she can only trust herself. And one of the most important decisions she has to make is how long a wine should macerate on its skins; when it’s ready for pressing.

“When I decide to press, for example, I don’t press because my friends are pressing. I taste and decide, all alone in front of my tank. Do I have to press now? Why should I press now? Or why should I wait?”

It’s a difficult process and she can still be affected by what other people think. Since Alice makes an infusion-like maceration for her reds, she usually lets her reds macerate with the skins for a long time, about eight months, until May.

“But then I had a guy here who said ‘Oh my god, do you let the wines macerate for eight months, that’s too long!’ I think I was affected by what he said, because that year I didn’t press until July. That was too long, it was a bit oxidated.”

It was a kind of opposition, her rebellious streak perhaps. So she always analyses the rationale behind her decisions, to clear her head. Alice thinks her method of only listening to herself, only trusting herself, is what makes her wines unique.

“I do almost a psychoanalysis of the wine and myself. Do I like it or not? What do I want, what do I like? Do I wait or not? I have to be honest with myself. If I ask a friend, I won’t follow my gut feeling. And following my gut feeling is why Octavin is Octavin. Sometimes my wines are very different from other wines. You like them or you don’t like them. Many people don’t like them, but when you do, you really like them. And maybe it’s because I ask myself all these questions? Of course I can taste with people and listen to people, but the decision, it’s one I have to take by myself. It’s much more difficult, but necessary.”

Tasting Panel, No Thanks

Alice takes me to the En Curon vineyard in Arbois, where the leaves are turning yellow and red. Here she grows Poulsard, Trousseau and Pinot Noir for her Dorabella and Zerlina. It’s one of the prime lieu-dits in the region, but she’s not part of the appellation anymore.

In 2013 Alice and Charles left the AOC, the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée.

They had to follow certain rules and the wines were supposed to taste a certain way, follow a certain style. And the wines had to be accepted by a tasting panel — a panel that often rejected the Octavin wines for tasting atypical. Yet, it was a tough decision to leave the appellation. At first, it was Charles Dagand who wanted to leave, while Alice thought they should continue to fight for their wines within the system.

“I’m in a region that I love, with wines I love. But at one point I started to ask myself: Why do I keep on fighting? I want to spend time with my children.” She adds: “I don’t want to make wine and open bottles only to hear five people around a table say ‘approved’ or ‘not approved’. I said to myself, ‘I’m 40 years old, I have two kids, I’m old enough to make up my own mind.’”

“I preferred to leave [the AOC] and do what I love. It’s freedom. Now it’s just me and my clients, not five people around a table with sterile, unproductive politics.”

Alice Bouvot

Winemaker, Domaine de l’Octavin

For many, leaving the appellation system is out of the question. In the Jura, the norm is to stay within the system: 90 per cent of all wines produced are classified as AOC.

“There are vignerons who have chosen to stay, to fight within the system, but I have chosen to leave. And I’ve never regretted it. I preferred to leave and do what I love. It’s freedom. Now it’s just me and my clients, not five people around a table with sterile, unproductive politics. It was a lot of negative energy. It was good to get out and get some positive energy.”

Freedom comes with a price though.

“When we left the AOC, we were criticised, so you have to be courageous. People, even vignerons, think that the criteria of the AOC equal quality.”

In Alice’s view, the AOC is focused on faults, rather than quality, because the system is about selling products. While for Alice, quality does not mean the absence of faults. It means wines with emotion, wines that are alive.

“Oenologists don’t talk about quality, only faults. When I trained to become an oenologist, I learned that there are seventy different faults. Why do they only talk about faults? It leads to a standardisation of wine. I prefer faults to a wine without emotion. To me, if there’s life, there’s emotion, and then there’s quality.”

At the same time, she acknowledges that everyone has to make their own choices and be true to themselves. Wine is subjective, Alice says, because it is all about taste and aromas. Like perfume. A mother at her children’s school uses a lot of perfume, so much that Alice knows whether that mother has been there or not just by entering the school courtyard.

“Obviously she loves her perfume, and I don’t. But who’s right and who’s wrong? Nobody. It’s not about right or wrong, it’s about taste. Just because I don’t like the smell, doesn’t mean that she shouldn’t be allowed to use it. It’s exactly the same with wine. If you don’t add yeast or sulphur, you get a wine which smells and tastes differently from what people are used to.”

Even though her wines can be found in some of the best restaurants in the world, for Alice, wine is not about fancy words; nothing you need to learn on a course or by getting a sommelier degree, it’s not about learning to find faults. You just have to be curious and find out if you like the wine or not. We’re back to where it all started for Alice.

“Every time I open a bottle, I ask myself: Do I like it? Do you like it? I don’t care. It’s really very simple: I like it, or I don’t like it.”

Support Independent Wine Writing

We are honored to republish this book excerpt with permission by the author. Order a copy of We Don’t Want Any Crap in Our Wine by Camilla Gjerde via her website and support the kind on independent wine writing that sheds light on the stories that mean the most.