Of the many eccentricities in Sicilian wine, Passito di Pantelleria might be biggest outlier. That’s because the famous sweet wine doesn’t really come from Sicily, but rather the rugged, wind-swept vineyards of Pantelleria, an island that is closer to Tunisia than the nearest Sicilian shore.

Known as the preferred vacation hideaway for Northern Italians and celebrities like Giorgio Armani and Madonna, the volcanic island may be the most isolated place in Italy. When I flew to the island last September, I was not reminded of Capri or Elba, but rather the approach to Hawaii — a sudden and lonely landmass of black rock and green plants arising from overwhelming blue.

Without a natural harbor, the people of Pantelleria were farmers, not fishermen, with most of their plantings focused on capers, oranges and Zibibbo, a grape also known as Moscato di Alessandria. Winemaking took a long hiatus under Arabic rule in the Middle Ages because of Islam’s tenets against alcohol. But Zibibbo not only survived the ban — it flourished, well passed the end of Arabic rule. The small, purple-gold berries are excellent for eating, especially as raisins. Much of Pantelleria was terraced for their cultivation, giving the island’s slopes a quirky-looking corduroy texture.

It was the advent of seedless grapes in the 1960s that crushed Pantelleria’s grape industry, forcing farmers to mass produce passito wines that they had made for home consumption.

According to Josè Rallo — co-owner of Donnafugata and the daughter of the estate’s late founder, Giacomo — these wines were rustic affairs that did not travel well. Her father would constantly hear about them from Northern Italians who vacationed on Pantelleria. They would rave about the vino contadino they sipped on the island, but upon taking them back to Milan or Bergamo, “they would be very oxidized; brown in color, no perfume, no finesse,” she says.

Rallo was pretty transparent about the seduction of Pantelleria: it’s beauty could make any wine taste like elixir. “Of course, you are on holiday, you are with friends, you are not stressed. Even if I bring you an awful wine, you are going to say ‘wow, fantastic!'” By the way, Rallo is a captivating speaker with a moxy and gusto that is contagious. “The problem is when you go back to Milano. You are stressed, your son is screaming, your wife is angry, it is raining … then you need a super passito!”

It was under these circumstances that Rallo’s father — a Marsala-based winemaker who had begun to carve out an international reputation for bold red wines and light whites — saw the opportunity to make Ben Ryé, Donnafugata’s Passito di Pantelleria of exquisite finesse. “My father wanted to bring the idea of Pantelleria everywhere,” she proclaimed, adding that if Pantelleria’s vineyards were going to survive, their product needed to travel the world.

And the vineyards of Pantelleria are certainly worth preserving. Upon setting foot on the island, my interest turned away from Note-Taking Writer toward Camera-Toting Photographer. Pantelleria is an artist’s landscape, with strange textures around every corner. The terraced walls, made of volcanic rock, are blackish-green in the shadows, bluish-gray in the light. Orange dust backfills them, and emerald colored vines — their arms outstretched like terrestrial octopi — give the scene a sense of order with their rows. These are the traditionally trained bush vines of Zibbibo grapes, and the method is recognized by UNESCO as an asset of “Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Farmers plant the vines in a shallow, bowl-shaped depression in the soil called a conche, which shelters the plant from Pantelleria’s brutal wind while also collecting precious moisture — a scarce commodity on the island.

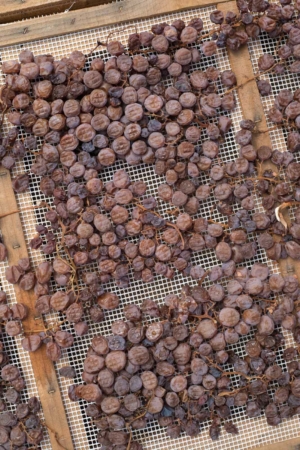

Harvest is back-breaking, as the grapes are low to the ground, and the slopes are treacherous. Grapes are picked at two different times — usually mid-August and early September. The bunches of the first harvest are laid out on mats outside to concentrate the sugars. Josè’s brother — Donnafugata co-owner Antonio Rallo — took us to one of these facilities to see the grapes at various stages of drying, and to meet the team that watches over them. The phases of the drying grapes was like another artist’s dream, the shifts in texture and color for each individual berry revealing different intervals of time.

From there, the grapes are destemmed by hand and then pressed for vinification. The second-harvest grapes — which matured late on the vine — are vinified immediately and the two are blended together.

As fascinating as this process is, I was enamored with the vines. I’m a geek for so-called “heroic viticulture,” a form of winemaking on steep, terraced slopes that takes many forms across Italy. On Pantelleria, these vineyards conjured a similar feeling as gazing upon the Roman Forum, or seeing the elaborate facade of Milan’s Duomo. But this was a more rustic vision of human ingenuity, one forged out of a necessity to make the uninhabitable habitable. Without them, what would Pantelleria be?

Note: My travels to Pantelleria were part of a press trip to Sicily, a portion of which was funded by Donnafugata and several other wineries. Learn more about my editorial policy.

Love this, Kevin. Thanks so much!